The collapse of the Soviet Union and the fall of the Berlin Wall served for some commentators, most notably Francis Fukuyama, as the capstone for the triumph of liberal capitalist democracy as the superior form of state over communism and socialism. Fukuyama’s claim that we reached “the end of history” in 1989 remains in the discourse today precisely because it is so difficult to definitively disprove. All serious efforts against the capitalist status quo, at least in the US, have failed. Hope in this direction seems ever diminishing. Mark Fisher, writing in 2009, referred to this condition as capitalist realism: “the widespread sense that not only is capitalism the only viable political and economic system, but also that it is now impossible to even imagine a coherent alternative to it”.

We haven’t always been in this depressive Fisherian mood, though we have progressively been building up to it. Discontents of Fukuyama’s end of history culminated a decade thereafter in the WTO protests in Seattle in 1999. This was also the year of the release of the films Fight Club, The Matrix, and Office Space, each of which contained strong anti-capitalist themes. Fight Club revolves around personal self-actualization and the movie ends with the literal destruction of the financial system. The Matrix serves as an allegory of transcendence through the understanding of the hidden mechanisms of control in society. Office Space is a fairly straightforward comedy about the horrors of corporate life and HR bureaucracy. All three films feature as their protagonist a disgruntled white-collar cubicle worker. All three films end with said white-collar cubicle worker, in one way or another, asserting their agency to break out of the systems under which they are oppressed.

These films are very different from each other and yet they still have surprisingly consistent messages. They present 1999 to us as a year when broad alternative futures were still imaginable, when people still felt like they had ability and agency to take meaningful action.

But the WTO protests failed to effect any real change, and the march of historical events — as opposed to history — carried on. Once again a crisis was reached a decade later in the recession of 2008, leading to the failed Occupy Wall Street movement of 2011, and finally the failed Presidential candidacies of Bernie Sanders in 2016 and 2020. The focus of the left, broadly construed, has now moved more towards identity. Economic inequality is an important issue as ever and yet it continues to recede into the background amidst the noise of culture war topics like critical race theory. If any corporate change has occurred, it is primarily in superficial ways, replacing those reviled grey cubicles with colorful, open office spaces, leaving much else the same, materially or spiritually speaking.

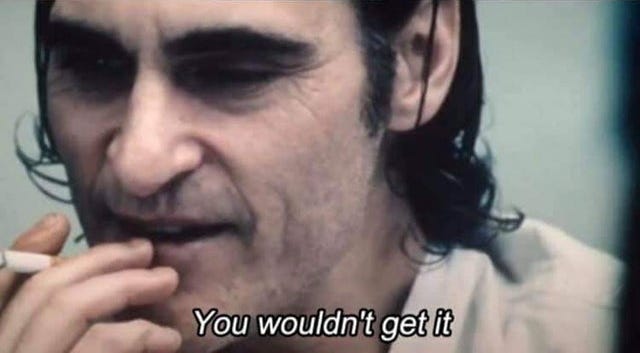

By now we’re firmly inside of capitalist realism’s grasp. Ostensibly anti-capitalist films like 2019’s Parasite and Joker seem to be unable to commit to more revolutionary thinking and action as the films of 1999 could. Instead, they both resolve in a sort of sad resignation. Parasite ends with Ki-woo Kim’s unrealistic fantasy of earning enough money to purchase the extravagant house in which his father is trapped. Joker ends in a violent mass riot, but it’s ambiguous as to whether this is just a figment of Arthur Fleck’s imagination. The discourse around the film, anyway, was too focused on its incel narrative — identity, again — to have anything much to say about the economic themes. “You wouldn’t get it”, Fleck says. Is he talking to his psychiatrist or to us, the audience?

This year, we have seen the release of The Matrix Resurrections, the fourth installment in the franchise. Yet it resurrects absolutely nothing of the imaginative spirit of the original, only presenting a dry and meaningless facsimile thereof with a bunch of silly inside jokes for fans of the franchise. When you ask someone today about the meaning of The Matrix films, you’ll most likely get the response that it’s a trans allegory, rather than one about capitalism. This is not to say that one answer is more correct than the other, but to remark on where our attention currently tends to be focused.

So where does the economic future lie today? Many commentators will point to China, for better or for worse. But if political currents are correlated with cultural works, as I am trying to argue, then I don’t see China as a real answer. As Dan Wang noted in his 2021 letter:

By my count, the country has produced two cultural works over the last four decades since reform and opening that have proved attractive to the rest of the world: the Three-Body Problem and TikTok. Even these demand qualifications. Three-Body is a work of genius, but it is still a niche product most confined to science-fiction lovers; and TikTok is in part an American product and doesn’t necessarily convey Chinese content.

The strict control and regulation of speech make true reimaginings of the future extremely difficult to achieve in China. Indeed, Fight Club was recently censored there, with its ending completely rewritten in an absurd fashion. Despite recent stagnation, cultural dynamism and change remain more possible in the west, although we may ironically have to look backwards a couple decades to rediscover those possibilities. As Mark Fisher wrote in 2013, “When the present has given up on the future, we must listen for the relics of the future in the unactivated potentials of the past”.

> was too focused on its incel narrative — identity, again — to have anything much to say about the economic themes

Inceldom can be conjectured purely as merely class consciousness in the sexual front, with "Chad" (the hyper-attractive) as bourgeoisie, women and "normies" (those who denies lookism) as petit bourgeoisie, and the "simps" as the lumpenproletariat. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7xPMYeb80bo

The weird paradox, is that as the inceldom community degenerated into three major forms that further capitalism: pick up artistry (PUA, the commodification of social behavior), "white pill" self improvement (self-exploitation and class denialism), and MGTOW ("exit" and maintenance of resentment through regress). The two main way out of this is either homosexuality (The Zizek Solution) and "rope" (The Fisher Solution).

Question: what other possible futures are out there that isn't part of the "Sigma Male Grindset"?